Most people would remember the devastating earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010 claiming the lives of more than 220,000 Haitians. This tragedy brought the country’s longstanding struggle with disasters to the forefront of global attention. Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. Over the past decade, Haiti has experienced nine disasters, including Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and the 2021 earthquake, with catastrophic impacts, clearly displaying the country’s vulnerability to such events.

Poverty and disasters are inextricably linked. Disaster occurrences exacerbate existing poverty and can lead to a long-term cycle of vulnerability. Haiti’s exposure to multi-hazards and pre-existing sociopolitical vulnerability and fragility make the nation susceptible to the impact of disasters. While the National Disaster Risk Management (DRM) System and DRM law approval in 2020 (supported by the World Bank and other organizations) marked significant progress, resources are still insufficient for disaster prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery.

What the High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) data in Haiti shows

In 2021, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank conducted two rounds of the HFPS across Haiti. The survey aimed to gather data on household welfare during the pandemic and to gain insights into the connections between poverty and resilience in the face of disasters. The analysis of this data yielded the key findings presented below.

- Most individuals in Haiti live in households facing the threat of multiple natural hazards. An estimated 23 percent of respondents reside in households threatened by one to two hazards, while 68 percent reside in households facing three or more hazards. Heat waves, cyclones, extreme rainfall, and droughts are the hazards most reported by households.

- The poorest households suffer more than their wealthier counterparts. The survey shows most natural hazards threaten low-consumption households in greater proportion. For example, while 25 percent of individuals in the bottom 40 percent of consumption reported living in a household exposed to earthquakes, this was lower at 17 percent for the top 60 percent. This was also true for other threats like floods, landslides, high swells, and wildfires.

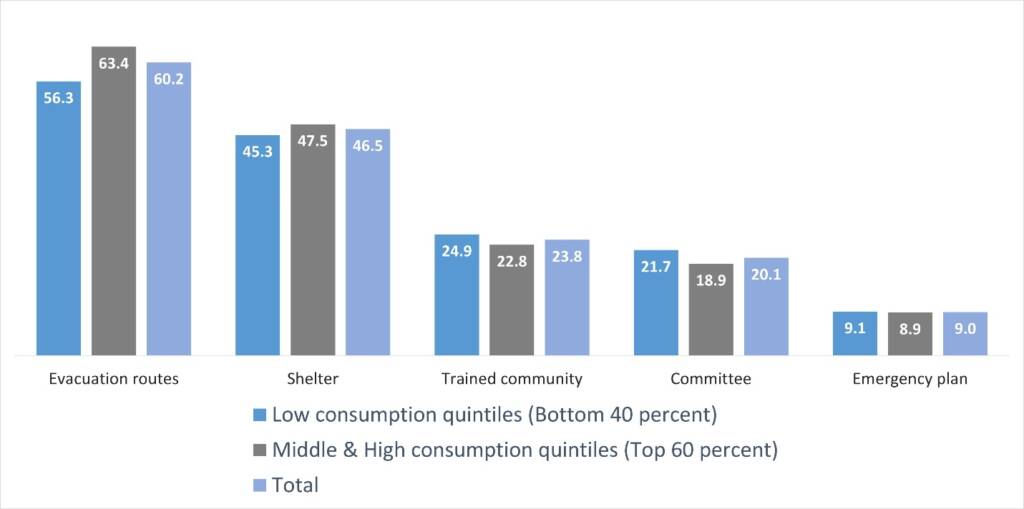

- Most households in lower-income communities, live in areas where communal disaster preparedness is low. Only 9 percent of households have access to an emergency plan, and less than 25 percent of households have committees or community-trained members to respond to a disaster. The evacuation routes (61 percent) and emergency shelters (47 percent) are the most common, but still scarce, community coping mechanisms.

Community coping mechanisms by consumption group (%)

Source: World Bank’s High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS), 2021 & Consumption Expenditure estimated following methods of Haiti’s Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages après Séisme (ECVMAS)

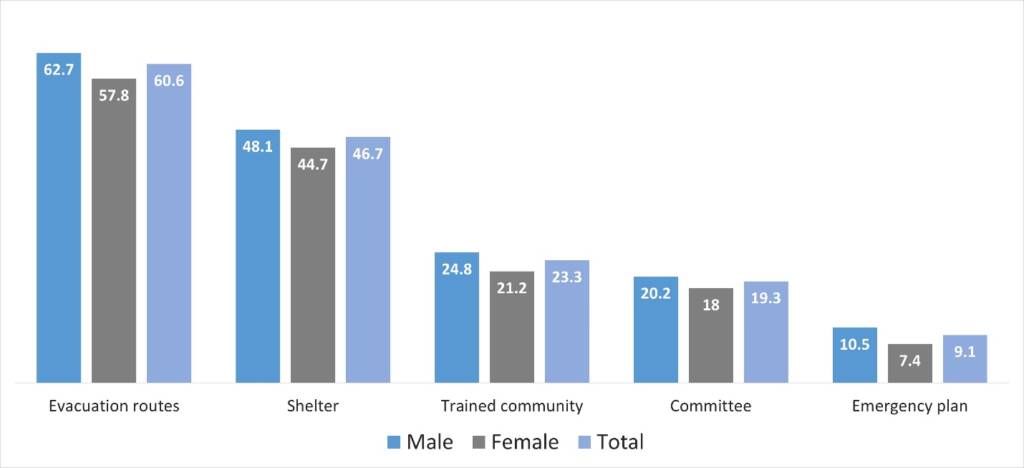

- The HFPS results also reveal the presence of gender disparities in preparedness at the household level. Female-headed households face additional challenges as they report lower access to evacuation routes, with a 5-percentage point difference compared to male-headed households. When it comes to access to shelters, female-headed households also experience lower rates compared to their male-headed counterparts (45 percent vs. 48 percent).

Community coping mechanisms by sex of household (%)

Source: World Bank’s High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS), 2021 & Consumption Expenditure estimated following methods of Haiti’s Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages après Séisme (ECVMAS)

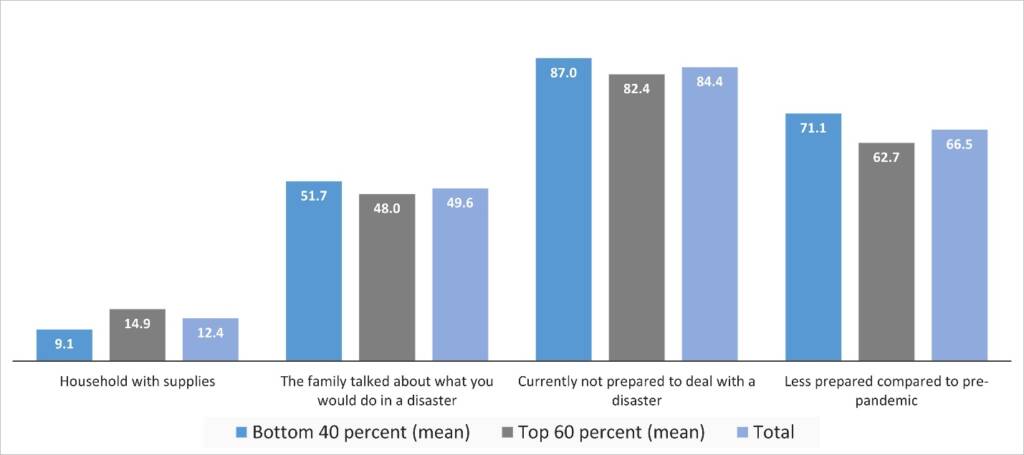

- Over 80 percent of households in Haiti mentioned not being ready to cope with a disaster. This is remarkable, as it shows that poor or rich Haitians are almost equally underprepared to face a catastrophic event. Only 15 percent of households in the top 60 percent of consumption reported having supplies to cope with a disaster (9 percent for poor households).

- The pandemic has worsened the ability of households to cope with disasters. Overall, 66 percent reported being less prepared after the pandemic than before. This is worse among the poorest, for whom 71 percent report being less prepared, compared to 63 percent among the wealthier quintiles.

Level of preparation within the household to cope with a disaster by consumption group (%)

Source: World Bank’s High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS), 2021 & Consumption Expenditure estimated following methods of Haiti’s Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages après Séisme (ECVMAS)

Five things to do to strengthen disaster preparedness and response in Haiti

Governments and international organizations need to ensure unprivileged, marginalized populations have a better disaster preparedness and response capacity. For Haiti, this could mean the following:

- Increase government investment in disaster preparedness and response, including comprehensive disaster risk assessment and management plans. For example, investments in multi-hazard early warning systems, emergency response infrastructure, and the emergency preparedness and response capacity of Civil Protection teams.

- Support community-level preparedness and response capacity, such as the disaster communal management committees (CCPC), as well as the development of contingency plans. Support should include equipment and training to enable CCPC to prepare for and respond to disasters effectively.

- Facilitate wider support for vulnerable populations, including providing financial support, such as targeted subsidies, credits, or loans, enabling the acquisition of secure land and constructing resilient houses.

- Enhance public education and awareness on disaster risk management targeting vulnerable communities and households.

- Address gender inequalities in disaster preparedness by providing targeted assistance to female-headed households and ensuring women are included in disaster risk management programs.

Being better prepared to face catastrophic impacts is a collective responsibility. This means involving all stakeholders and members of society to ensure everyone, especially the most vulnerable, has the tools and means to prepare for and respond to disasters effectively.